JS Functions

Why#

In JavaScript, a function is a block of code that does a particular task. Often while coding, you’ll find yourself writing the same code statements and expressions repetitively. Functions allow you to assign a block of code, even a sub-program in our project, to be called, or invoked, with a single identifier. The use of functions is a central concept in JavaScript programming.

Functions in JavaScript are first-class citizens/objects. This means that you can pass function values by reference just like any other value (objects, arrays, etc)

First-class functions give us a wide variety of flexible and powerful options. Design patterns let us write more readable, dynamic, and concise code (e.g. Asynchronous Functions and Higher-Order Functions).

What#

A function is a value that contains a block of code. Functions can take in arguments (parameters), execute code, and return values.

Above is a function named isEven, that takes in a parameter named n and evaluates n through a selection statement and returns a result. Our isEven function will return true for any even whole number that is passed into it.

First-class functions can be:

- Stored in a variable

- passed as arguments of a function

- Returned from a function

- Hold their own properties

- Be stored in data structures

NOTE: A First-class function is an object that supports all of the operations generally allowed to other objects. This includes being able to be assigned to a variable, passed around as a function argument, and being returned from a function.

Up until now, we’ve been using console.log() to print text to the browser console. This(console) is a built-in JavaScript object with a .log() function that takes in parameters, and prints them out in the web console.

JavaScript has many built-in functions that we can and will use. The best part about functions is that we can create new functions for solving an endless amount of problems.

How#

Below is a glance at function syntax

Defining Functions#

You can create functions in multiple ways:

Assigning the function value to a variable

Or declaring a function with the declaration keyword

You define a function using the function keyword, followed by the function name, parentheses with parameters, and curly braces containing the function body.

Which way should you use? Either works, but there is a key difference. When you assign a function to a variable, you cannot call the function before you assign the variable. However, if you declare the function, the value is hoisted and you can call the function before the function declaration.

For example:

Defining Function Parameters#

Functions can contain multiple parameters or none at all. This is where JavaScript can be tricky. You can declare the function to receive 2 parameters. However, you are allowed to pass only 1 parameter, or 3. Or 10 or 20, even though you only declared the function to pass in 2. The extra params will not be used, and the params not passed in will be undefined. Lastly, you can initialize a parameter in the case that the param is not passed in:

Pure Functions and Side Effects#

You can write code in the function body that produces a side effect or returns a value solely dependent on its parameters (pure function).

A side effect is when a function body changes or handles values from outside of the function scope. A pure function returns a value that will be the same return value every time you run a function, based on 0 or more parameters passed in. Given the input, you will ALWAYS receive an expected output.

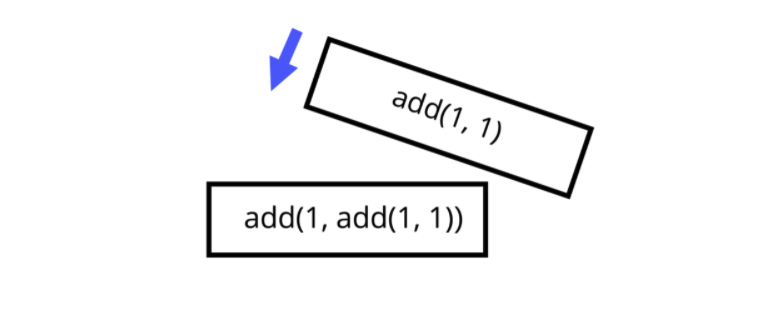

Above, the add function contains the return keyword. This keyword breaks the control flow and returns a value as a result. The add function returns a number that is the sum of two parameters passed in.

Scope#

Let’s take a minute to go over scope. Scope refers to the space inside where code is ‘visible’. We’ve mostly been working with global scope, which has made variables and values ‘visible’ within our entire program. There is also local scope, where variables and values inside the body of a function are only ‘visible’ within the confines of the function’s curly braces. For example:

Above is our add function again. Inside the function, I declare a variable named sum and initialize it with the value of a + b. sum is only available inside the local scope of the sum function, while var1 is available inside countBs’ scope. Pay attention to the relationship between scoped variables and values. In general, you can access ‘outer’ values from the inside, but not ‘inner’ values from the outside.

Closure and Recursion (in brief)#

Closure involves a function that references bindings from local scopes around it.

So we know that scopes determine the visibility of variables. Closure is used to reference a value from an outer function scope in an inner function scope, after the outer function has been executed.

Read more on closures.

Recursion involves a function that calls itself. There are unique solutions that require recursive functions. Be mindful that this could very well end badly and crash your program/browser.

You could have written the isEven function as follows:

Read more on recursion.

Arrow Notation#

As of ECMA2015, you can use arrow notation to declare functions:

Now you have the option to drop the function keyword and add the lambda expression (=>) after the parameter list, but before the function body (curly braces). If a function only has one statement that you intend to return a value from, you can drop the curly braces around the function body to implicitly return the result of the single statement (as above). And if you have a single parameter, you can drop the parentheses surrounding the parameter list. Such as:

Arrow notation is great for succinct pure functions that are passed as parameters to higher-order functions as callbacks.

Call Stack#

We’ve spent this whole time talking about declaring and defining functions, but what happens when you invoke or call a function?

When you invoke a function, the context of the function in the program is placed in the call stack. The call stack is the place where the computer stores the context, or position, as it runs the code. When a function is invoked, the context is stored in memory on the top of the stack, when the function returns. It uses that context to continue the execution of your program.

Takeaways#

- Functions are blocks of code that can accept parameters, and be called by a single identifier

- You can declare functions with the function keyword, followed by the identifier, parameter list (

()), and body{} - You can return values from a function call by placing the value after the return keyword