JS Fetch API

Why#

One of the most powerful things a web developer can do is fetching data from a server and displaying it creatively on their site. In many cases, the server solely exists for that specific site. The server could contain blog posts, user data, high scores for a game or anything else. In other cases, the server is an open service that serves data to anyone that wants to use it (i.e. weather data or stock prices). In either case, the methods of accessing and then using that data are essentially the same.

What#

APIs#

Servers that are created for serving data for external use (in websites or apps) are often referred to as APIs, or Application Programming Interfaces.

There are multiple ways of requesting data from an API, but all of them basically do the same thing. For the most part, APIs are accessed through URLs, and the specifics of how to query these URLs changes based on the specific service you are using. For example, the OpenWeatherMap API has several types of data that you can request. To get the current weather in a specific location, you need to request data from this URL:

https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=hoover,al

You’ll want to switch out the city for the location you’re requesting. The specifics for using any API are usually documented on the service’s website. We'll be referencing the OpenWeatherMap API documentation.

If you haven’t already, go ahead and paste the weather URL above into your browser…(we’ll wait).

Unless the implementation of that specific API has changed, you probably get an error like this:

This brings us to another point about APIs. In most cases, you have to sign up and get an API key to use them. Obtaining the API key is as simple as signing up on their website and using it is usually as easy as appending it as a query parameter in the url:

http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=Hoover,al&APPID=1111111111

How you will include your api key will change from service to service

Services like the OpenWeatherMap use API keys to track who is requesting the data they serve, and how much data they are requesting. The reason they do this is so that people can’t take advantage of their service. Running servers, especially large ones, costs money, and while each current weather request (or whatever) is relatively cheap, if the amount of requests gets too high the cost could be significant. Imagine using that API to create an amazing weather app that gets used all over the world….you could easily have thousands of people accessing that data every minute!

By signing up for a service and getting an API key you are letting the service track how much you are actually using. In many cases services are limited as to how much data they can request for free. With the weather app example, their free plan only allows you to make 60 requests per minute and also limits what types of data you can access (details here if you’re interested). So, if your app became successful, you would probably need to pay for a better account.

How#

Luckily for us, the majority of our apps are only going to be used by us and the people that view our portfolios. So we’ll get by just fine with free services.

Once you get a key and have waited for its activation you can paste the URL into the browser again (including your key of course) and hopefully, you’ll see a proper response:

Fetching Data#

So how do we actually get the data from an API into our code?

A couple of years ago the main way to access API data in your code was using an XMLHttpRequest. This function still works in all browsers, but unfortunately, it is not particularly nice to use. The syntax looks something like this:

Developers, feeling the pain of having to write that stuff out, began writing 3rd party libraries to take care of this and make it much easier to use. Some of the more popular libraries are axios and superagent, both of which have their strengths and weaknesses. More recently, however, web browsers have begun to implement a new native function for making HTTP requests, and that’s the one we’re going to use and stick with for now. Meet fetch:

In case you’ve forgotten, scroll back up and look at how you would use XHR to do the same thing. While you’re admiring how nice and clean that code is, notice the .then() and .catch() functions there. Do you remember what those are? (PROMISES!)

Let’s change up our API for this example. We’re going to walk through an example using fetch with the giphy API to display a random gif on a webpage. The API requires you to sign up and get a free API key, so go ahead and do that here.

Giphy has several methods for searching and finding gifs which you can read about in their documentation. Today we’re just going to use the ‘translate’ endpoint because it’s the simplest one for our purposes. You can find the appropriate URL in their documentation by scrolling down here. What it tells us is that the correct URL is api.giphy.com/v1/gifs/translate and that it requires 2 parameters, your api_key and a search term. If you put it all together correctly (with YOUR API key) you should get something like this:

https://api.giphy.com/v1/gifs/translate?api_key=YOUR_KEY_HERE&s=cats

Go ahead and try that URL (with YOUR API key) in a browser. If everything goes well you should get a relatively long string of data and no errors.

CORS#

A side note before we start putting this into our code. For security reasons, by default, browsers restrict HTTP requests to outside sources (which is exactly what we’re trying to do here). There’s a very small amount of setup that we need to do to make fetching work. Learning about this is outside our scope right now, but if you want to learn a bit about it this Wikipedia article is a decent starting point.

Whether or not you took the detour to learn all about Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) the fix is simple. With fetch, you are able to easily supply a JavaScript object for options. It comes right after the URL as a second parameter to the fetch function:

Simply adding the {mode: 'cors'} after the URL, as shown above, will solve our problems for now. In the future, however, you may want to look further into the implications of this restriction.

Let’s Do This - Giphy API#

For now, we’re going to keep all of this in a single HTML file. So go ahead and create one with a single blank image tag and a script tag pointing to our app.js in the body.

In your app.js, let’s start by selecting the image and assigning it to a variable so that we can change the URL once we’ve received it from the Giphy API.

Adding fetch with our URL from above is also relatively easy:

You should now be able to open the HTML file in your browser, and while you won’t see anything on the page, you should have something logged in the console. The trickiest part of this whole process is deciphering how to get to the data you desire from the server’s response. In this case, inspecting the browser’s console will reveal that what’s being returned is another Promise… to get the data we need another .then() function.

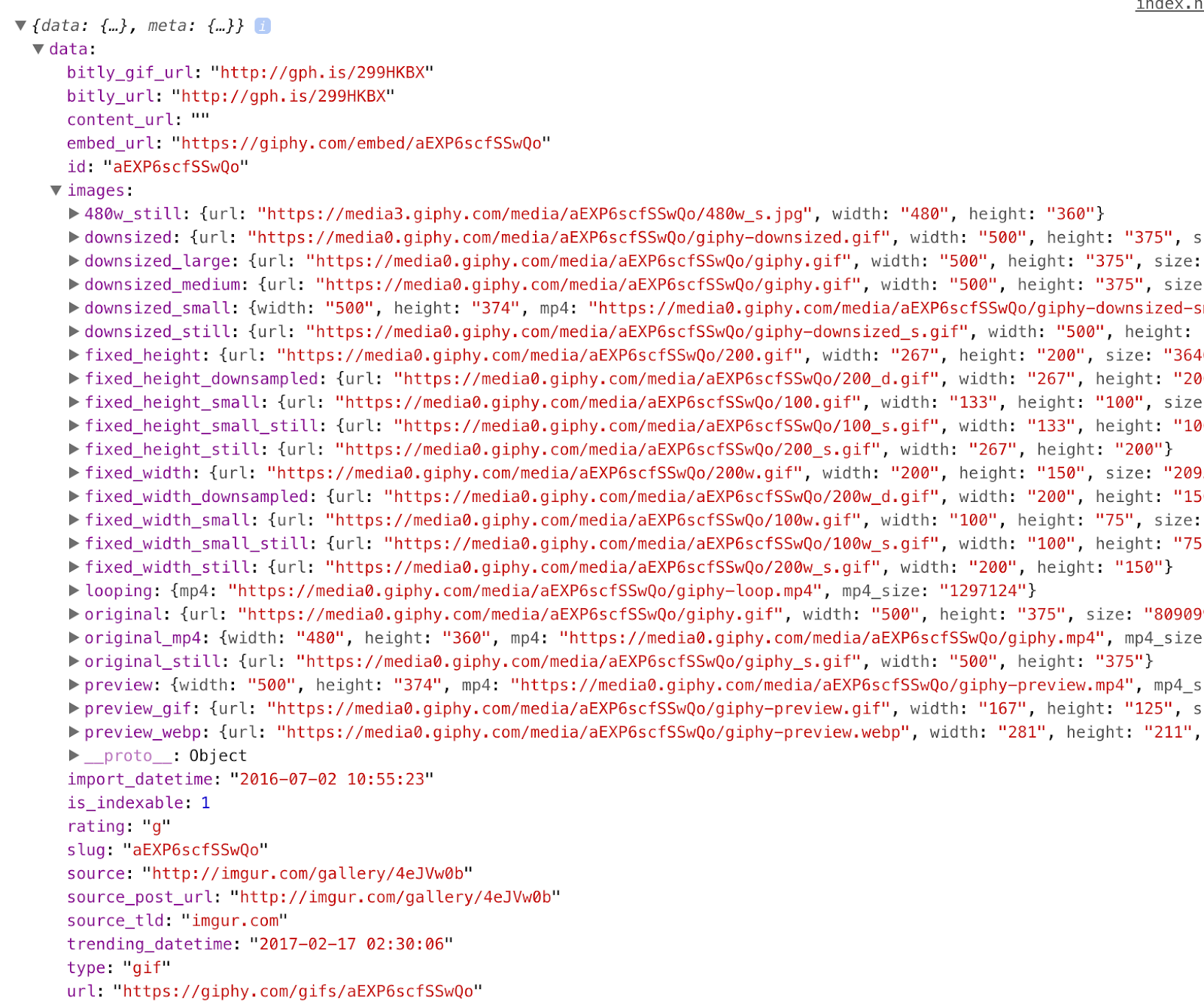

Now we have a JavaScript object and if you inspect it closely enough you’ll find that the data we need (an image URL) is nested rather deeply inside the object:

To get to the data we need to drill down through the layers of the object until we find what we want!

Running the file should now log the URL of the image. All that’s left to do is set the source of the image that’s on the page to the URL we’ve just accessed:

If all goes well, you should see a new gif on the page every time you refresh!

Takeaways#

- The browser has a Fetch API that allows use to send and receive network requests with JavaScript

fetch()takes in a url string, and options object- The returned response can be handled in a

.then()method res.json()parses the response body to JSON, a commonly used format for JavaScript